Introduction

History of Buddhism will be presenting a brief outline from the birth of the Buddha to current times. This will be quite a heavy read but it is important to know this history in order to understand how political and cultural influences had caused Buddhism to be the way that it is now.

Parts 1 and 2 of this series will be heavily referencing from the book ‘Indian Buddhism’ by Anthony Kennedy Warder1. There will be several highly debatable dates and scenarios and it will be duly noted.

In this article, some of the important events in the Buddha’s life from birth to extinguishment will be discussed.

Birth of the Buddha

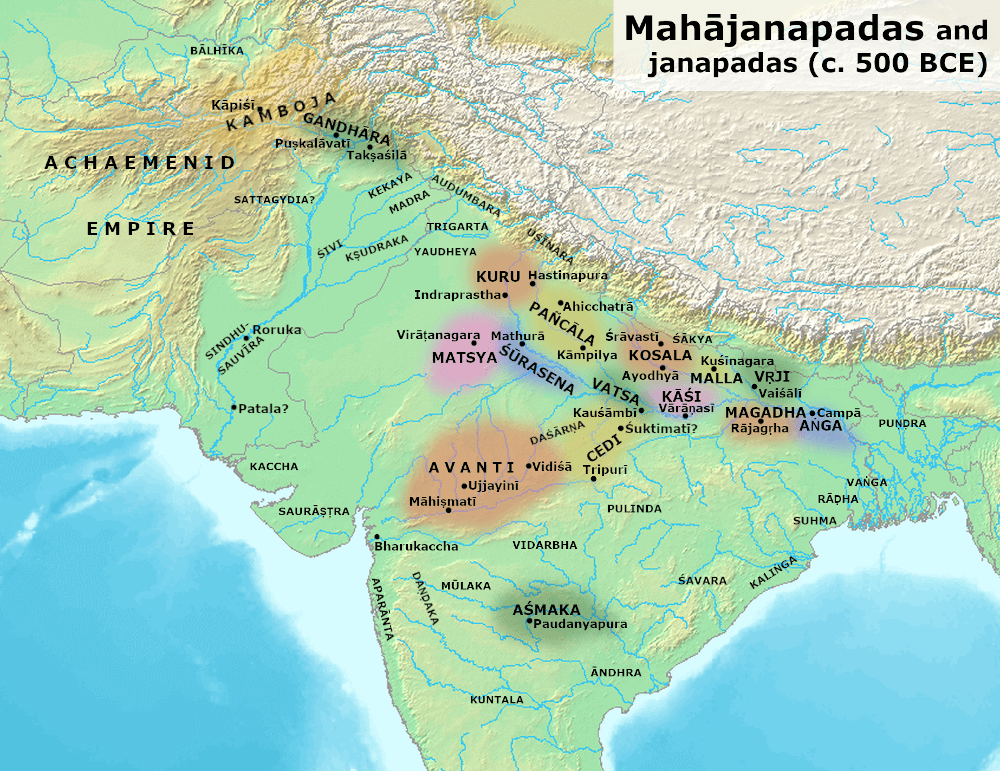

Around 566 B.C. (Highly debatable. Academics are unable to find concrete proof of the Buddha’s birth date even from other sources. See Indian Buddhism1, Chapter 3), Sākyamuni Bodhisatta was born to a warrior caste family called the Sākyan who governed the Sākya Republic, which was a very small city state and probably a vassal to the bigger and more powerful Kosala kingdom.

The Bodhisatta’s father is Suddhōdana, who was the leader of Sākya Republic. He was given the name Siddhattha Gotama and was raised in the Republic’s capital city Kapilavatthu. He lived his youth in luxury with one palace for summer, one for the rainy season and one for winter. This is considered the norm for wealthy families at that time, just like how the rich in modern times own multiple properties around the world as their holiday homes.

Not much was mentioned for Siddhattha’s birth mother in the scriptures. It was claimed that she passed away when Siddhattha was a baby and he was fostered by his maternal aunt2, Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī, who was also the second wife of Suddhōdana.

Quest for Enlightenment

At the age of 29, Siddhattha Gotama left his home in search of enlightenment. He first found Āḷāra Kālāma and quickly mastered the concentration state of dwelling in the ‘Dimension of Nothingness’. Finding that he could not achieve enlightenment with Āḷāra Kālāma, Siddhattha left and found another teacher Uddaka Rāmaputta. With Uddaka, Siddhattha managed to achieve the concentration state of dwelling in the ‘Dimension of Neither Perception Nor Non-perception’. However, this is also not the state of enlightenment.

After learning from these 2 teachers without avail, Siddhattha practised on his own using ascetic methods3. His methods were so severe that he almost died of malnourishment. It was then that he realised severe ascetic methods will not lead him to enlightenment and he remembered the first time he entered the first Jhāna when he was younger. After having this realisation, he ate some food and tried to enter the Jhānas. Siddhattha succeeded and realised the Four Noble Truths thus becoming a Buddha.

Teachings

Sutta Piṭaka (Basket of Discourses)

In the scriptures, Buddhism is called Dhamma-Vinaya by the Buddha as these two basket of teachings comprised of everything taught by him. The Sutta Piṭaka (Basket of Discourses) comprises of all the discourses taught by the Buddha.

The Buddha differentiates his teaching of the Dhamma between the communities of monks and nuns and lay devotees. He felt that lay devotees were steeped in sensual pleasures by being in family life, hence they would not understand the more difficult treatises of the Dhamma nor have the time to practise accordingly. As for the ordained, they were seeking release from the suffering of this universe and life as a monastic provided the perfect environment for this to happen. Therefore, the Buddha taught the most difficult and intricate Dhamma treatises to the monastics.

Dhamma for lay devotees

For lay devotees, the Buddha primarily focused on the ways to accumulate more merits, live more happily and more richly both materially and spiritually. The quintessential and most important discourse for lay devotees is Advice to Sigālaka. The Buddha gave advice for all aspects of life from how a child should behave to how a boss should treat their employees; from how to live a virtuous life to bad activities to avoid to prevent wealth drain. For lay devotees who are adverse to reading discourses, they only need to read this discourse as not only does it cover all aspects of Buddhism for lay devotees, they will reap great benefits after understanding and acting upon it.

The situation did change when venerable Sāriputta visited Anāthapiṇḍika at his death bed to deliver the last discourse. The venerable gave a particularly difficult discourse on letting go of the clinging to the senses, which essentially is the 3rd Noble Truth. Anāthapiṇḍika was the foremost male lay Buddhist devotee and yet he exclaimed that he had not heard such a discourse from the Buddha even after attending to him for many years. He beseeched venerable Sāriputta to ask the Buddha to teach these difficult Dhamma to the lay devotees as some may be able to understand enough to benefit from these treatises.

In the 21st century, people’s education levels have increased dramatically compared to during the Buddha’s time. Therefore, we can see more lay devotees reading and researching very deep Buddhist treatises. However, the lay devotees’ practise environments have not changed or gotten even worse as there are even more sensual pleasures to indulge in and busier lives have increased the difficulty of finding time to practise. Therefore, it is important to understand that the Buddha was not stopping the lay devotees from attaining theoretical knowledge of the treatises. In fact, theoretical knowledge can be easily acquired as all he had to do was to repeatedly teach the same topics and use a variety of methods like analogies and explaining from different perspectives to let lay devotees understand the depth of the Dhamma. What was stopping The Buddha was the fact that he also considered there would not be much time for them to meditate after work and family duties. This makes the Buddha’s position on lay devotees’ practise highly accurate even after 2,600 years.

Dhamma for monastics

For people interested in seeking Enlightenment, understanding and practising the following treatises are of vital importance.

Four Noble Truths

Four Noble Truths is the main tenet of Buddhism and the basis of all the Dhamma that the Buddha taught. In the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta4, the first discourse that the Buddha gave, he described how the Four Noble Truths enabled him to attain Enlightenment. The Truths states that:

- Life in this universe is innately suffering and unsatisfactory.

- The cause for this suffering and unsatisfactoriness is craving. More specifically, craving for sensual pleasures, craving for existence or craving for non-existence.

- Suffering and unsatisfactoriness can be ended by letting go of the 3 types of craving.

- The way to let go is by training in the Noble Eightfold Path.

Dependent Origination

Dependent Origination5 is the treatise for the 2nd Noble Truth. The most well-known 12-link model describes the causation process from the moment our physical senses are impacted by external triggers leading to our actions which then causes us to be infinitely reborn in this universe. The Buddha used 2 sentences to succinctly describe Dependent Origination:

When this exists, that comes to be; with the arising of this, that arises.

When this does not exist, that does not come to be; with the cessation of this, that ceases.

Noble Eightfold Path

According to the Buddha, the Noble Eightfold Path6 is the only path that can lead to Enlightenment. Hence, in order to attain the 1st stage of Enlightenment, Stream-entry, all 8 factors must be fulfilled to a certain level. The factors are:

- Right View

- Right Intention

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

Vinaya Piṭaka (Basket of Monastic Rules)

After gaining enlightenment, the Buddha went to the five attendants who served him while he was practising ascetism and left him after he started taking food. At Benares, the Buddha taught them the Four Noble Truths and one of the attendants, Kondañña, became the first Arahant in the Saṅgha. This discourse is famously known as the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, Setting in Motion the Wheel of the Dhamma Discourse. The second discourse taught to the attendants is called Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta7, The Characteristic of Non-Self. After this discourse, all five attendants attained Arahantship.

From then on, the Buddha tirelessly taught the Dhamma to whoever is willing to listen and the Saṅgha (referring to either the community of monks and nuns and/or the community of ‘noble ones’ who have attained at least Stream-entry, the first stage of Enlightenment) was created after the five attendants became Arahants. He also created the rules governing the Saṅgha called the Vinaya. The first rule was created when a monk engaged in sexual intercourse with his ex-wife at the request of his parents in order to conceive a heir to the family. In today’s recorded Vinaya Pitaka (Basket of Rules), there are 227 major rules for monks, 311 major rules for nuns and numerous minor rules.

After Suddhōdana passed away, Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī sought to be ordained but the Buddha refused. She, and other Sākyan ladies, followed the Buddha after his Rains-retreat and requested to be ordained several times but were all refused. Venerable Ānanda saw her crying after one such refusal and offered to help her speak to the Buddha. Finally, after much persuasion, the Buddha relented and set the Eight Weighty Principles for nuns to follow for life if females were to be ordained as nuns (Highly debatable. May not be a formal ordination rule, just a temporary principle8). Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī accepted and became the first female to be ordained as a nun and the Nuns’ community (Bhikkhunī Saṅgha) was created.

Morality for lay devotees

The Buddha did prescribe morality for the lay devotees and that is the 5 precepts. These precepts are meant to be the basic moral compass for lay people.

The 5 precepts are:

- Refrain from killing living things

- Refrain from stealing

- Refrain from sexual misconduct

- Refrain from lying

- Refrain from intoxicant consumption

Although the 5 precepts have always been touted by Dhamma teachers as the practice that can enable lay people to have high chances of good rebirths in their subsequent lives, it is not the highest morality that can be achieved by them. These precepts only govern personal behaviour but do not address many other moral issues like filial piety towards parents, interactions with friends and colleagues, and responsibilities towards family members.

For people who are interested in leading a truly well-rounded life, obtaining the highest morality possible for a lay person and be guaranteed even better rebirths, they should read the detailed discussion on the discourse ‘Advice to Sigālaka‘.

Abhidhamma Piṭaka (Basket of Analytic Discourses)

Although there are Buddhist texts claiming authenticity of the Basket of Analytic Discourses as coming from the Buddha or venerable Sāriputta, in the Basket of Discourses, the Buddha always referred to his teachings as the Dhamma-Vinaya and there was no mention of the Abhidhamma at all. Moreover, modern academic research has refuted these claims through thorough study of the texts.

It was found that the earliest form of Abhidhamma appeared in lists or matrices of key teachings in the Basket of Discourses. From there, further development, after the extinguishment of the Buddha, resulted in summaries and expositions of these lists, together with explanations. In the following hundreds of years, monks like Buddhaghosa, a 5th-century A.C. Indian monk, and Ledi Sayadaw, a 19th century A.C. Burmese monk, wrote detailed commentaries on the Abhidhamma and these were included in the Basket as canonical texts. These texts are mainly philosophical works which includes many new ideas that were not found in the Basket of Discourses nor the earliest forms of Abhidhamma. This is the reason for the many discrepancies that can be found when studying both the Basket of Discourses and Basket of Analytic Discourses. Therefore, it is up to individuals which Basket they choose to trust.

At Refuge In Dhamma, we put our full trust in the Basket of Discourses because even after 2,500 years, the contents of the Basket of Discourses from both schools, Theravāda and Mahāyāna, have high levels of similarity. According to researchers, this ‘high percentage of the similarities testifies to the high authority and reliable fidelity of the Pali transmission‘9. As such, all articles in Refuge In Dhamma will get references only from the first 4 volumes of the Basket of Discourses.

Chief Disciples

The Buddha had 2 chief disciples, Sāriputta and Moggallāna. Both of them were born on the same day in adjacent villages just north of Rājagaha. When they grew up, they became close friends and embarked together on a spiritual quest to find Enlightenment. After having unsatisfactory lessons with Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta (Highly debatable. They could have seeked several teachers10), they decided to split up for their quest and agreed to keep each other informed of their search.

One day, Sāriputta met a monk named Assaji, who was one of the 5 attendants that the Buddha first taught and attained Arahantship. Venerable Assaji told Sāriputta about the Buddha’s teaching in brief and directed him to the Buddha. After listening to this brief discourse, Sāriputta attained Stream-entry. Then, he went to look for Moggallāna and told him about the encounter. Upon hearing the brief discourse, Moggallāna also attained Stream-entry. They went back to inform Sañjaya about their decision to leave and look for the Buddha at Veḷuvana (Bamboo Grove) and left with Sañjaya’s 250 disciples.

After meeting the Buddha, Sāriputta and Moggallāna were ordained and the Buddha named them his chief disciples. Venerable Sāriputta was considered to have the highest wisdom among the disciples, second only to the Buddha. Venerable Moggallāna was considered to possess the most powerful psychic powers among the disciples, second only to the Buddha. After ordination, Venerable Moggallāna took 7 days to become an Arahant while venerable Sāriputta took 2 weeks.

Venerable Moggallāna’s quest to Arahantship although shorter, was fraught with difficulties. He frequently fell asleep during meditation and the Buddha had to teach him methods to ward off drowsiness11. Venerable Sāriputta, on the other hand, had a longer but smoother training period. He attained Arahantship when he was fanning the Buddha while the Buddha was teaching the wandering ascetic Dīghanakha about the comprehension of feelings12.

As chief disciples, venerable Sāriputta and venerable Moggallāna had to help the Buddha handle Saṅgha affairs and take disciples of their own. In the Saccavibhaṅga Sutta13 the Buddha commended the both of them, saying:

Monks, you should cultivate friendship with Sāriputta and Moggallāna. You should associate with Sāriputta and Moggallāna. They’re astute, and they support their spiritual companions.

Sāriputta is just like the mother who gives birth, while Moggallāna is like the one who raises the child. Sāriputta guides people to the fruit of stream-entry, Moggallāna to the highest goal.

Extinguishment of the Buddha

The journey in the final days of the Buddha is recorded in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta14, The Great Discourse on the Buddha’s Extinguishment.

The discourse starts at Rājagaha where King Ajātasattu of Magadha wanted to attack the Vajjis and he told his brahmin minister, Vassakāra, to ask the Buddha for his advise. The Buddha managed to prevent the war from happening by listing the principles that the Vajjis followed and saying that they would be undefeatable so long as they abided by those principles. He continued to extend those principles that prevent decline to the monks’ and nuns’ communities.

Another noteworthy incident in this journey is the Buddha’s acceptance of Ambapālī the courtesan’s invitation for a meal at Vesālī without any discrimination against the person’s gender and vocation. He even rejected the invitation by the Licchavis who came after Ambapālī. The Buddha made an interesting comment about the Licchavis saying that they looked like the Devas (Deities) residing in the realm of the Thirty-Three.

The first serious illness to strike the Buddha happened at the Rains-retreat in the village of Beluva. He was so severely ill that he almost died. However, the Buddha managed to suppress his illness after considering that he needed to give advanced notice to his followers and the monks’ and nuns’ communities. After venerable Ānanda, Buddha’s personal attendant, declared his reliance on the Buddha, he was admonished to not be too reliant. The Buddha said that he had done enough for the communities by teaching the Dhamma without holding any details back. He also told venerable Ānanda about his worsening body condition. He ended the admonishment by stating this:

So Ānanda, be your own island, your own refuge, with no other refuge. Let the teaching be your island and your refuge, with no other refuge.

…

Whether now or after I have passed, any who shall live as their own island, their own refuge, with no other refuge; with the teaching as their island and their refuge, with no other refuge—those monks and nuns of mine who want to train shall be among the best of the best.

By and by, the Buddha and venerable Ānanda reached Kusinārā where a bed was made in-between two sal trees for the Buddha to rest. He then taught venerable Ānanda the proper way to venerate the Buddha:

Any monk or nun or male or female lay follower who practices in line with the teachings, practicing properly, living in line with the teachings—they honor, respect, revere, venerate, and esteem the Realized One with the highest honor.

So Ānanda, you should train like this: ‘We shall practice in line with the teachings, practicing properly, living in line with the teaching.’

It can be seen from this quote that the Buddha expected all Buddhists, whether monastic or lay, to practise and incorporate the Dhamma into their daily activities. He did not want them to acquire only theoretical knowledge.

Following this, the Buddha gave 4 pilgrimage locations for Buddhists to visit, namely: The birth place (Lumbini15), enlightenment place (Bodh Gaya16), first discourse place (Sarnath17) and extinguishment place of the Buddha (Kushinagar18). He then proceeded to commend on venerable Ānanda’s qualities. Venerable Ānanda was later sent to Kusinārā to inform the Mallas about the Buddha’s upcoming extinguishment and the wanderer Subhadda overheard this news. The Buddha cleared all of Subhadda’s doubts and he became the last personal disciple of the Buddha.

In his final moments, the Buddha instructed the junior monks to change to a more respectful way to address senior monks. He also gave a harsh punishment to a recalcitrant monk named Channa: No one was allowed to admonish or instruct him until he had changed his behaviour. Finally, he asked all the monks and nuns present to voice out any doubts but no one asked any questions as they had all attained at least Stream-entry, the first stage of Enlightenment.

After this, the Buddha entered the Jhānas in succession, reverse order then in succession again until the Fourth Jhāna. He finally extinguished after emerging from the Fourth Jhāna. The Buddha entered parinibbāna around 486 B.C.

References

- Indian Buddhism (A.K. Warder)

- Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī

- Ascetic methods

- Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta

- Dependent Origination

- Noble Eightfold Path

- Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta

- Eight Weighty Principles

- The Chinese Madhyama Agama and the Pali Majjhima Nikaya

- Sāriputta

- Nodding off

- With Dīghanakha

- Saccavibhaṅga Sutta

- Mahāparinibbāna Sutta

- Lumbini

- Bodh Gaya

- Sarnath

- Kushinagar